Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about an intense reading experience I had at the beginning of 1998. I was a junior in college, headed to a semester abroad in Moscow, and at some point along the way I bought a copy of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, The Unconsoled, which had just come out in paperback and felt so new—because even though it was clearly influenced by, you know, Kafka, it also seemed totally unlike anything I had ever read. Some people really hated that book; years later, I still clearly remember Michiko Kakutani’s review in The New York Times, which felt so confusing and upsetting and actually frightening to me—because she was a famous book reviewer, and it was so clear that she hadn’t understood or appreciated anything about the book, so how was she writing a review of it, what was the point of book reviews?

The Unconsoled is about a concert pianist who has arrived at a nameless Central European city, and I remember being particularly struck by the dream techniques—specifically, the device where the narrator introduces a new character, and then, as the scene goes on it becomes increasingly clear that the narrator and this character have a long and fraught history—and by the cognitive evocation of foreign travel: the constant effort to piece together the particular atmosphere and situation of a new place, and to decipher the responsibilities you have there. This felt so true and so reflective of the fact that, in real life, sometimes you meet someone new and, within minutes, “pick up on” some dynamic that feels like it goes way further back,

In Moscow, I was staying in the house of a retired typist/ secretary, who had really wanted to host a boy student, and would periodically lament that she got stuck with me instead. (Hosting foreign-language students was a pretty common way for retirees, esp women, to make extra money.) She had never married, but had had a long affair with her late employer, a geologist at the Academy of Sciences. I was staying in her spare room, on a “divan” that had been made up as a bed, with a sheet hanging down around the edge like a dust ruffle, and you had to be very careful not to accidentally stub your toe on the ruffle, because what was behind it wasn’t empty space, or a suitcase or anything like that, but, rather, some large jagged metallic-seeming boulders, which turned out to be geological samples that the geologist had left there—and then he died.

I remember lying on that divan and cruising through The Unconsoled, where it gradually emerges that this Central European city has a complicated historic problem, related to the personal lives of the people who live there, and they’re relying on the pianist’s performance of some particularly abstruse contemporary compositions to solve it. (Ishiguro was def having fun w the composer names and music titles, e.g. “Was it Yamanaka’s Globestructures: Option II? Or was it Mullery’s Asbestos and Fibre?”). This aspect of the plot seems to have particularly annoyed Michiko Kakutani, who couldn’t understand how the narrator thought that other people were expecting so much of his performance (and concluded that he was “arrogant” and “projecting his own delusions of grandeur as an artist” onto everyone else).

But I found it so funny and moving, and so true to life, where you show up in a world populated by people whom you’ve never met, but who turn out to have a long history with you already, and someone somewhere expects some nameless important thing from you, and you have to decipher what it is. I remember in the room with the geological samples, the sense of some larger, older complex of problems, which were related to why the retired secretary was hosting foreign students—and even if she didn't actually expect me to solve anything, and even if it would have been arrogant and deluded to think that I could solve anything… well, there are still these real longings in the air that a person can feel.

This now reminds me of a moment early in The Unconsoled when the pianist lies down on the bed in his hotel room, and looks at the ceiling and realizes it’s the ceiling of a room in his aunt’s house where he stayed for two years as a child.

Suffice it to say that The Unconsoled is one of the books I’ve thought about regularly for the past 25 years—especially after I started going to other countries for book tours, because it now feels very clear to me that it’s a book about being on book tour in another country. Last week, I re-watched The Third Man, and felt the same way: Graham Greene was 100% thinking about book tour. The particular reason I've been revisiting The Unconsoled and The Third Man is because of the ongoing Lviv-writing project. I’ve been thinking about the atmosphere in Lviv—about how, like a lot of cities that have been a part of many different nations/ empires, it gives you a feeling of being simultaneously in multiple countries and time periods. Like occupied Vienna in The Third Man, and like the Central European city in The Unconsoled.

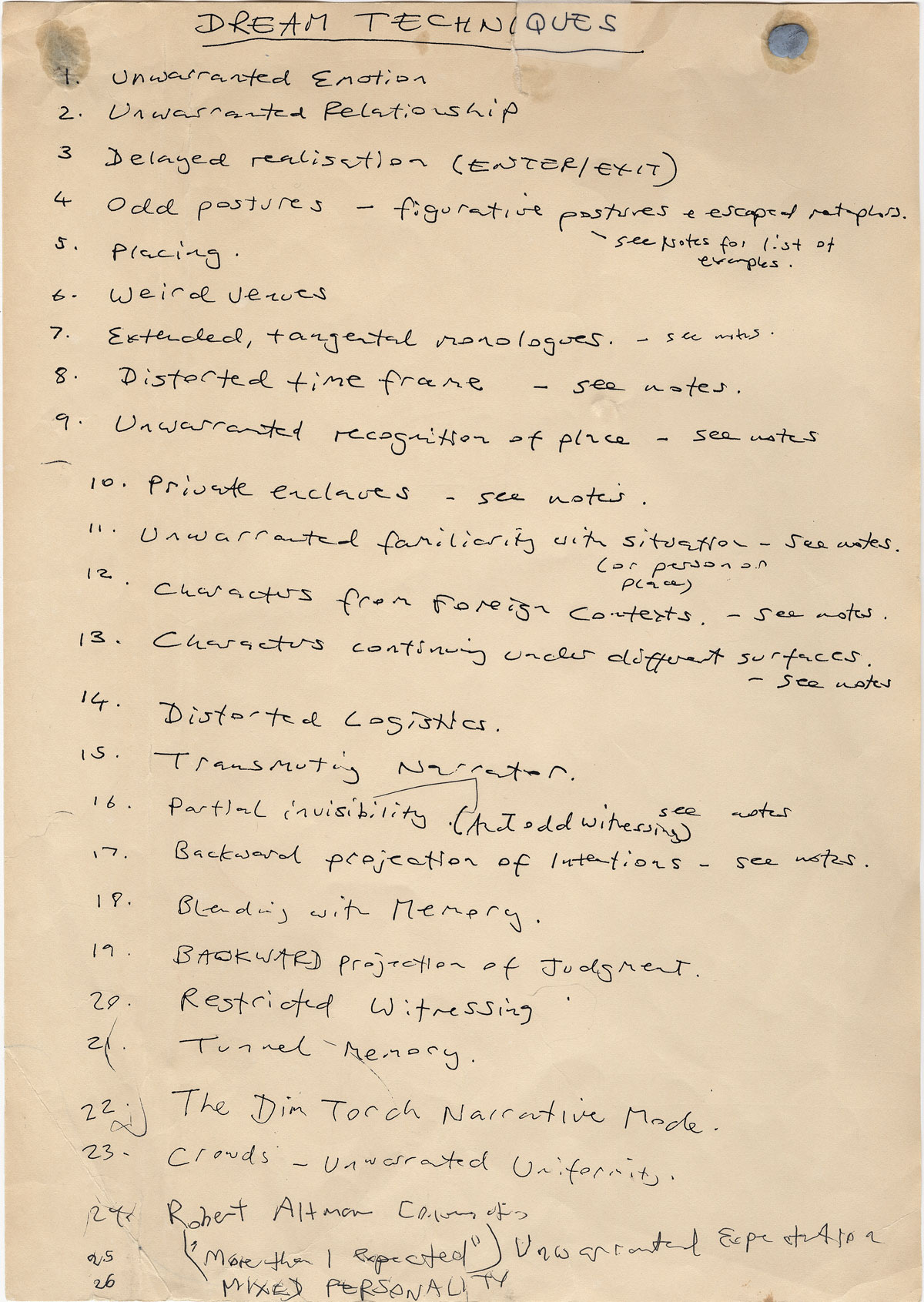

This observation eventually sent me down a rabbithole trying to figure out whether Ishiguro might have been thinking of Lviv, in particular, when he wrote The Unconsoled. The answer I reached is “no,” but it was a great rabbithole, and I found some things I wanted to share with you—e.g. a LitHub post about the “dream techniques” Ishiguro used in The Unconsoled. This list turned up in the archives at the University of Texas:

Of course the first thing I did was look for my two favorite techniques, and there they are: “11. Unwarranted familiarity with situation (or person or place),” and “25. Unwarranted Expectation.”

The post includes an excerpt from an interview with Ishiguro, where he’s talking about how to write an “international” novel—which is another weird aspect of writing professionally, because when you’re getting started, you’re obviously only thinking about the languages and cultures that you know… but being a viable “author” basically means being translated into languages you know nothing about, and answering questions you never thought of, and it all gets in your head when it's time to write another book. This is obviously way more intense for non-English-language writers, who are under huge pressure to think of the English-language “international” audience (while also doubtless thinking about the critics who are like, “This lamestream writer is now only writing inauthentic books that pander to Americans”).

But it’s a thing for English writers too, and apparently, after the mega-success of his third novel, The Remains of the Day, Ishiguro and his wife were sitting in a diner, discussing possible subjects for an “international” book that people from different cultures could relate to:

My wife pointed out that the language of dreams is a universal language. Everyone identifies with it, whichever culture they come from. In the weeks that followed, I started to ask myself, What is the grammar of dreams? Just now, the two of us are having this conversation in this room with nobody else in the house. A third person is introduced into this scene. In a conventional work, there would be a knock on the door and somebody would come in, and we would say hello. The dreaming mind is very impatient with this kind of thing. Typically what happens is we’ll be sitting here alone in this room, and suddenly we’ll become aware that a third person has been here all the time at my elbow. There might be a sense of mild surprise that we hadn’t been aware of this person up until this point, but we would just go straight into whatever point the person is raising.

I found that FASCINATING and it made me think a ton of different things, which you can find after the paywall. Thank you for reading!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Elif Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.