Erudite readers! You don’t need me to tell you that June 3 marked the centenary of the death of Kafka, bringing with it a deluge of Kafka-themed books, conferences, video games, etc.; this is to apprise you of my own modest contributions.

First, I have a story in the anthology A Cage Went In Search of a Bird: Ten Kafkaesque Stories (UK edition here). It has gotten some nice write-ups, including this one. I was approached by the editors last June—just when, having finished the Either/Or paperback tour, I had dragged the old (mortal) envelope to Spain, where I (it?) was wrestling with various new-book-related issues, in between flailing through a midnight Japanese class over Zoom, and trying to figure out how to start a Substack, and also how to put together an application for a co-op in New York: a process I was just about to describe—inaccurately—as nightmarish beyond words, when in fact it is summarized very satisfactorily in many web articles, including this one, which made me laugh out loud multiple times, starting with the first sentence (“New York City real estate has always been pioneering”).

So with one thing and another I was feeling a bit overwhelmed, and my initial reaction to the Cage-in-search solicitation email was roughly paraphrasable as, “Kafka death anthology—morbid! Capitalism! Next!” And the thing that was next, in the world of email, was a giant pdf (with samples) about co-op board recommendation letters.

Quick sidebar. Co-ops, which make up some 75% of NYC apartments, require potential buyers to submit a lengthy application, including a personal statement (an essay about how living in this apartment is the glorious culmination of the story of you), plus letters of recommendation. And one of the things it said in this pdf was that boards prefer letters from recommenders who have themselves owned shares in co-ops, and who have ideally themselves served on co-op boards—because these are the only people who can truly testify to the weighty responsibility faced by a board when it comes to deciding who gets to live in the building.

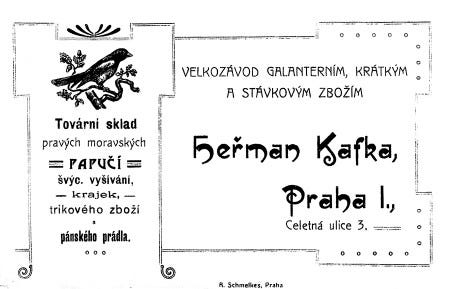

Then I understood that the board was a “cage in search of a bird,” and the bird needed letters of reference, and the Kafka-inspired story wrote itself in two days! It’s called “The Board” and was recently reprinted in Electric Literature, with a kind introduction by Alina Ştefănescu, who is the author of this evocative Kafka-related poem, and also another poem about a black bird; kafka is the Czech word for “jackdaw,” hence Kafka’s father’s business card:

Moving on… the reason I know what Kafka’s father’s business card looks like is that I am just back from four amazing days at the Transatlantic Kafka Conference at the Jewish Museum in Prague, where I got to hang out with many Kafka-heads more knowledgeable than my own. It was my first time in Prague, so this was very exciting for me, even though I spent most of the first two days in the hotel room, eating hardboiled eggs that I had abducted from the breakfast buffet, and writing my talk.

Conference highlights included hearing the writer Magdaléna Platzová talk about her new novel, Life After Kafka (English translation coming out in August), about Felice Bauer; Platzová mentioned meeting with Felice’s son, who was born three years after Kafka’s death and went on to become a psychiatrist, and felt a lot of animosity towards Kafka, but still had an extensive Kafka library, except that he kept it inside his closet, next to his clothes. The son is the one who pressured Felice to publish the letters, after Letters to Milena came out and became a bestseller. (At least this is what I have in my notes, hopefully I didn’t get it wrong—I’m excited to read the book.)

The climax of the novel, Platzová said, involves Felice’s confrontation with the letters: a confrontation not just with Kafka, but with a “vanished world.” This wasn’t the first time the conversation turned to the last paragraph of the last volume of Reiner Stach’s 3-volume Kafka biography—it’s from the epilogue, so it’s after Kafka’s death:

[T]he occupation of Czechoslovakia, the German terror, the genocide of the Jews, and World War II tore apart [Kafka’s] world. The fate of many people he was close to was sealed, and countless traces of Kafka’s life that were left behind in the collective memory were wiped out. Letters, photographs, literary estates, even entire archives were destroyed. The violence that gripped the era often made it impossible to identify what was lost, and even to ascertain that it was lost. If Kafka had had the double good fortune of surviving the tuberculosis and then a concentration camp, he would not have recognized anything left after the end of this catastrophic blow to civilization. His world no longer exists. Only his language lives.

Which is to say, there was a lot of sadness at the conference. but the language does live, and continues living.

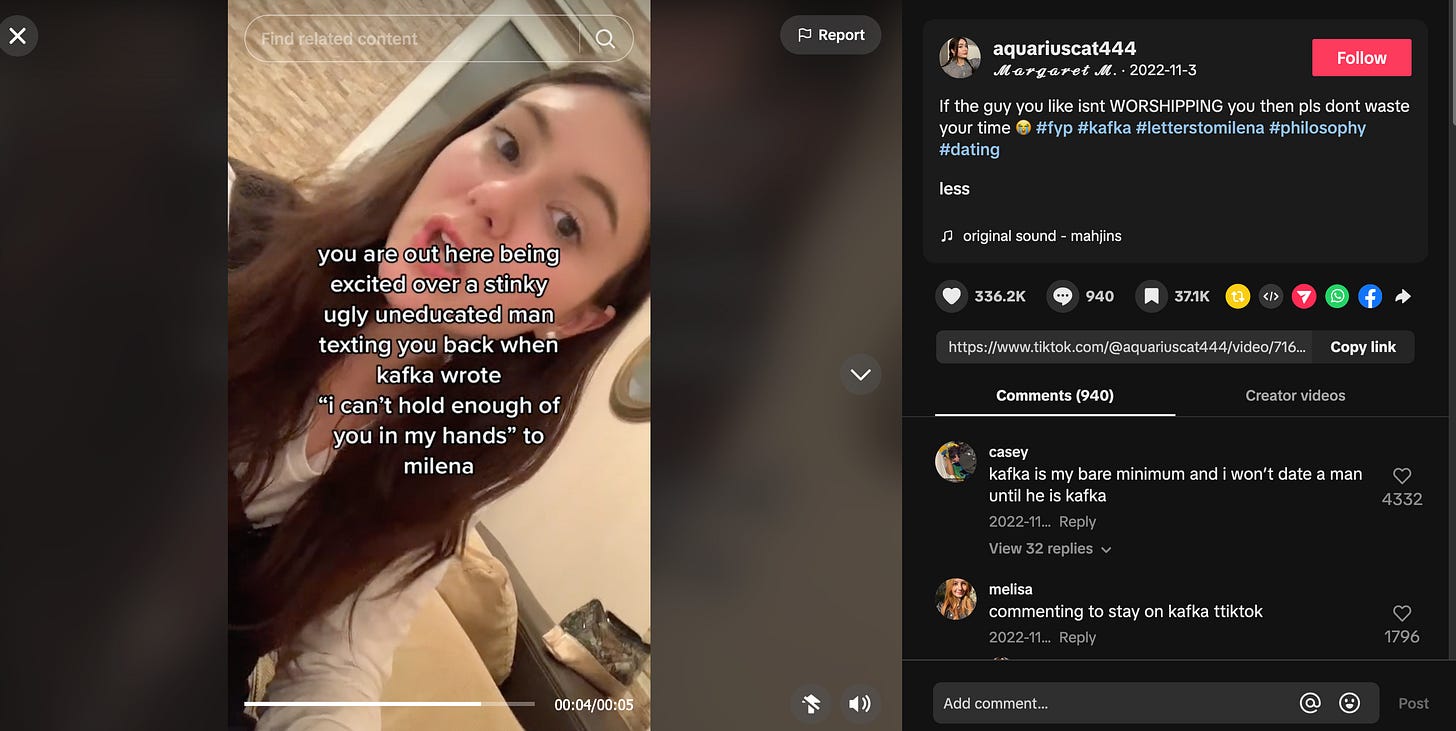

It was, for example, a delight to hear the tireless literature warrior Merve Emre describe how Kafka’s Letters to Milena have spawned a TikTok trend about how Kafka is the ideal boyfriend.

Merve’s talk had so many great quotes that I immediately acquired Letters to Milena and read almost all of it in one day. It’s so powerful to read all the Milena letters in a row, the way they were written, relentlessly—though I must say it also made me really grateful that I never dated Kafka. There’s a part where he dumps his fiancée (Julie Wohryzek) because of Milena, and then the fiancée asks if she can write Milena a letter—and he says “yes”—and then he asks Milena (23, coughing blood) to reply “kindly but firmly”—and then he changes his mind and tells the fiancée not to write to Milena—but obviously by then she has already written the letter and mailed it. Then she (fiancée) freaks out and somehow persuades the post office to give her back the letter—and then Kafka mails it to Milena himself—and that isn’t even the end of the story, it drags on for longer than you think possible. But either despite or (let’s face it) because of the insane parts, it’s an incredible book—it feels as important to me as the novels.

My own talk was about Kafka’s relationship with Max Brod: a subject I’d been thinking about for a long time in a vague way, so I felt very lucky to have an opportunity to think about it in a more focused and stressed-out way, and in such scenic surroundings. I feel like I finally understood some ideas I’d been working through, and I’m excited to write it up to share with you very soon. That’s going to be the next post—I’m working on it now.

In the meantime, as a special thank-you to paid subscribers, I am appending a mini Kafka Prague photo essay, plus a short bonus discussion of the titles of the Czech and Turkish translations of Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

Thanks for reading!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Elif Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.