Broadminded readers! I’m so excited to (finally) share my profile of Sayaka Murata, out in this week’s New Yorker. (It’s the innovation issue, and also features a breaking story about a biotech startup that resurrected a long-extinct prehistoric wolf, such that, when I got the cover copy, I was like, “Wow, looks great, can’t wait to read about the ‘dire wolf’”—and was told “The dire wolf is top secret until Monday.” But now Monday is here so feast your eyes on this little guy.

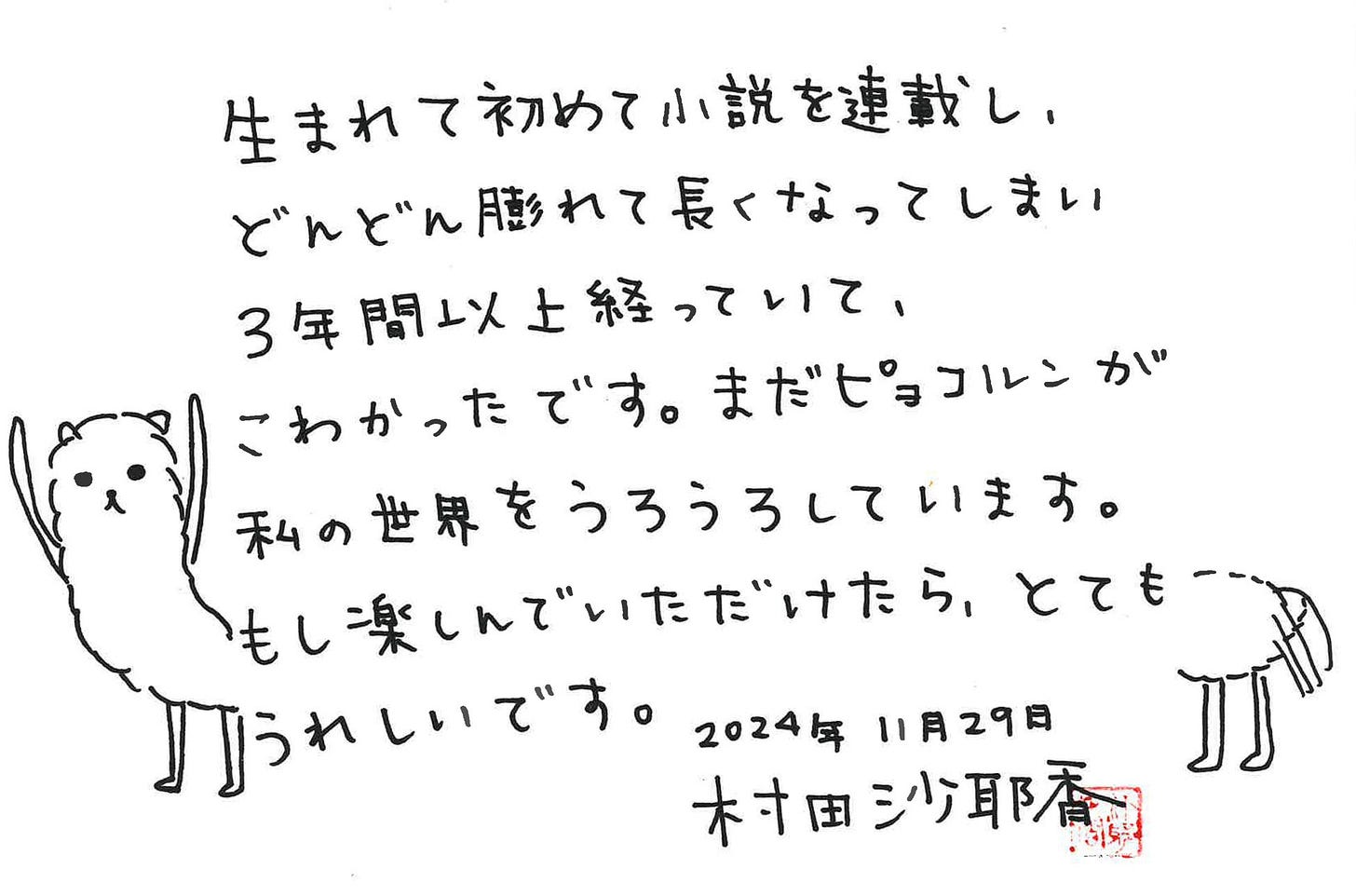

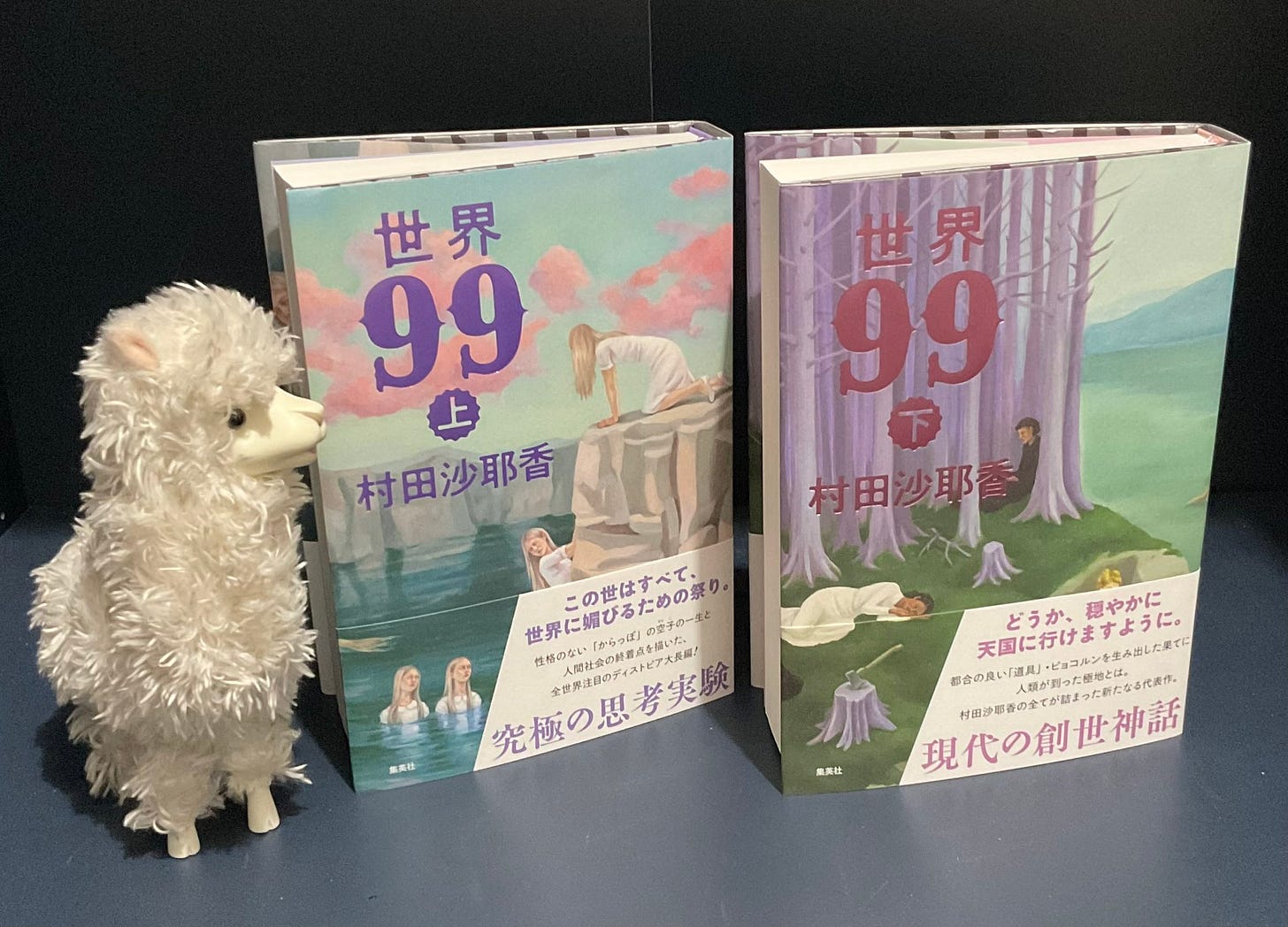

Interestingly, Murata’s 1000-page new novel, World 99 (世界99, just out in Japan, yet to be translated), features an adorable alpaca-like pet with genetic material from pandas, dolphins, and bunnies (as well as alpacas).

Caveat lector, something that Murata described as possibly “very triggering” happens to the cute pet. I have my worries about the dire wolf too, tbh… but let’s face it, he probably has more reason to be concerned about my species than I do about his.

I’ve been reporting the Murata piece for a long time (starting with a 2023 brunch-related debacle that you can read about in the story). One of the biggest challenges has been how to balance this work with my own novel, which I have been very absorbed by—and I mean absorbed, not in the sense of, “I know where I’m going and I just need to plug away,” but in the sense of “Every day/ hour of writing is giving more information about a direction that might lead me out—I just hope I can hold it all in my head for long enough!” Notwithstanding how much I truly love and am fascinated by Sayaka Murata (and how the profile was my idea, nobody asked me to do it), there were still moments when it was wrenching and painful to tear myself away from my own work in order to immerse myself in someone else’s—especially when language issues were involved.

Last spring, for example, I was in Rome trying to write my book, and ended up doing a side trip to Turin to see Murata present Parti e omicidi, Gianluca Coci’s translation of Murata’s 2014 novel 殺人出産, which doesn’t exist yet in English (though Murata’s brilliant English translator, Ginny Tapley Takemori, who was so incredibly helpful with the profile, hopes to translate it someday; a possible title is “Breeders and Killers”). The book and the presentation were Italian, and it was somehow especially hard to set aside my own thing and think in another language (something that English-language writers rarely have to do, unlike every-other-language writers—so that, in addition to having no practice and not being good at it, there is an additional issue where you also feel like a huge baby). (What do I mean by “like a huge baby”? Guilty? Ashamed?) (Poor babies!—poor former us.)

Of course, once I made myself do it, it was an amazing experience. In the magazine story, I talk about a question that the interviewer (Irene Graziosi) asked about anger—where is the anger in Murata’s work—which I couldn’t believe I had never asked myself—and la rabbia in particular sounded so operatic and rabid and Italian; how appropriate that the discovery of its absence should have come to light here—and I felt like I was seeing “Weltliteratur” (as comp lit people call “world literature,” because that’s what Goethe called it 🤣🤣🤣)—and then it started pouring rain, and I was rushing around with Sayaka trying to find an Uber outside the festival venue, which was in a giant former Fiat factory that opened in 1923, shortly after Mussolini’s rise to power—and I reached a new understanding about defamiliarization and anger and Shklovsky’s Third Factory (which came out in 1926, after Stalin came to power (believe it or not, some version of this made it into the New Yorker story!)—and I felt like I could start to see something about WWII that’s there in Murata’s work, but always below the surface, like the anger.

Then I went back to Rome and my book and forgot about it… and then the whole thing repeated on a bigger scale this winter, where I was getting ready to go to Japan, doing research, reading earlier profiles (including these excellent ones in Wired and in Gentlewoman), and rereading her books—and at that point I was still working on my own book, and the switching was a little painful—until I was actually on the plane to Tokyo, where I was writing something in a Scrivener file and wasn’t sure if it was for my novel or if it was actually about Murata (what if she was going to end up in the novel)—and I entered a euphoric state where I didn’t have to choose, I didn’t have to abandon the mystery of the novel to work on the mystery of Murata, because in fact they were THE SAME CASE, and everything was connected.

And every minute in Tokyo felt somehow revelatory (I was able to stay two weeks instead of one—thank you, paid subscribers!), it felt like college when I was learning Russian and going to Russia for the first time—only without the terror and precarity and indignity of being 20—and everyone I wanted to talk to would actually talk to me—and Kindle existed, so I could just get more and more books—and it felt like some version of pure learning—and I didn’t even feel guilty because it (“the case”) was related to everything I found most important, to war and genocide, to sex and family and children and death (“breeding and extinction,” as Murata puts it), and to the potential of art to change the boundaries of what we can imagine.

By that point I felt so lucky to be there, and grateful to the New Yorker for making it possible—and I was thinking a lot about the last time I went through so much trouble to interview someone whose work I was obsessed with, which was in 2021, when I profiled Céline Sciamma. At that point I was still working on Either/Or, and it wasn’t necessarily easy to drop everything and watch a lot of French movies and go to France—but it ended up being one of the best experiences of my working life, and it hugely informed the editing of Either/Or, which is a different book, I think even structurally, than it would have been if I hadn’t spent that time in Paris.

In Tokyo, I began to realize that Sciamma and Murata—despite a number of surface differences—felt similar to me; they felt personally important to me for similar reasons. I was thinking back to what Sciamma called “the scam”: a set of ideas about love/ romance/ sex/ narrative, which were once considered universal and necessary… but what if they weren’t universal; what if there were many, many more possible shapes for narratives and relationships, and we were just at the beginning of discovering them? (The historic contingency of seemingly universal/ necessary structures is a big theme in many of Murata’s books—including “Vanishing World,” translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, which comes out with Grove on April 15.)

I realized that I saw Murata, too, as someone who had seen through “the scam” (or “a scam”) in a way that I hadn’t; that was why it felt so important to follow her and understand what she knew, and how she knew it. (At some point I texted CS about this; her reply included this sentence: “The scambusters.”) One thing I got to do in Tokyo (along with Ginny Tapley Takemori, and my amazing interpreter Naoko Selland, and also Saho Baldwin from the publisher Bungeishunju) was to take a day trip to Murata’s hometown: Chiba New Town, a planned community created in the late sixties, an hour by train from Tokyo. (Versions of Chiba New Town appear as a setting in many of Murata’s books.)

In 2021, I had taken a similar trip with Céline Sciamma to the town where she grew up, Cergy-Pontoise: a “new town” created in the seventies, an hour by train from Paris, and a setting in Sciamma’s films. At some point, Murata mentioned growing up in a place “without history”—a phrase Sciamma had also used. Was that related to their ability to see through historic scams—to question inherited norms?

At the same time, I was equally struck by how different the atmosphere was in Cergy, which has a cool seventies vibe and is home to Annie Ernaux, compared to Chiba New Town (at least the part I was able to see), which was strangely devoid of charm and had a shopping-mall vibe—and that felt so related to the postwar mood in the two countries, one that was on the winning side, and one that wasn’t.

Then I came back to New York, and it was a somewhat tricky time because of some ongoing family medical issues (my deepest thanks to everyone who expressed concern, and thanks also for understanding that it will take me longer than usual to reply to personal communications), and then there was the horrible drama of how to put my impressions and thoughts in a form that could possibly fit on a few pages of a general-interest magazine. (Nearly every sentence in the finished piece was once a paragraph.) This was accomplished, eventually, with a lot of help from the brilliant Valerie Steiker (thanks also to Jessie Hunnicutt, Daniel Ajootian, and Han Zhang for much ingenuity)… but it basically took my every waking moment for eight weeks, exacting a toll on my own health in various minor but attention-needing ways, so it will be a minute before I am back on track with my own work, and also with Substack—though I will be posting extra in April, to make up for March. In the meantime, thank you for your support, and I hope you enjoy the profile!

(I am excited to eventually share some outtakes that didn’t make it into the magazine version, although, for contractual reasons, that can’t happen for another sixty days. But don’t worry, I have lots of other things I want to tell you before then.)

Till soon!

The email version of this had a bad link for the New Yorker story. Here is the correct link: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/04/14/sayaka-muratas-alien-eye

A friend of mine sent me the Sciamma interview when it came out. She said I absolutely had to read it. I started reading it without looking at the by-line. It was only when I finished (feeling like my whole understanding of relationships and the point of filmmaking had shifted) that I checked to see who had written it. I called her immediately and I told her that it was confirmation of how much your writing style resonates with me that even without knowing it was you, I had told her it was one of my favorite New Yorker articles ever. I even found a physical copy (by asking on neighborhood groups) so I could mail her the physical article that we'd both enjoyed so much.